It was great to see so many Acumen blog readers at the recent Acumen Users Conference! For those of you who missed the meeting, MIPS and Advanced APMs were among the hot topics on the conference agenda and there was plenty of excitement in the room. A few weeks ago we had some fun with Quality Payment Program (QPP) numbers. Since that post, a colleague shared an intriguing perspective on the impact of the proposal to raise the low-volume threshold exclusion for MIPS. Writing for the Health Affairs blog, David Introcaso suggested we should hold our applause for this change as he highlighted a few of the potential unintended consequences. His post inspired me to consider how the greatest specialty on the planet might be impacted by this change, so today let’s “nephrologize” the MIPS low-volume threshold (LVT).

It was great to see so many Acumen blog readers at the recent Acumen Users Conference! For those of you who missed the meeting, MIPS and Advanced APMs were among the hot topics on the conference agenda and there was plenty of excitement in the room. A few weeks ago we had some fun with Quality Payment Program (QPP) numbers. Since that post, a colleague shared an intriguing perspective on the impact of the proposal to raise the low-volume threshold exclusion for MIPS. Writing for the Health Affairs blog, David Introcaso suggested we should hold our applause for this change as he highlighted a few of the potential unintended consequences. His post inspired me to consider how the greatest specialty on the planet might be impacted by this change, so today let’s “nephrologize” the MIPS low-volume threshold (LVT).

Revisiting the LVT

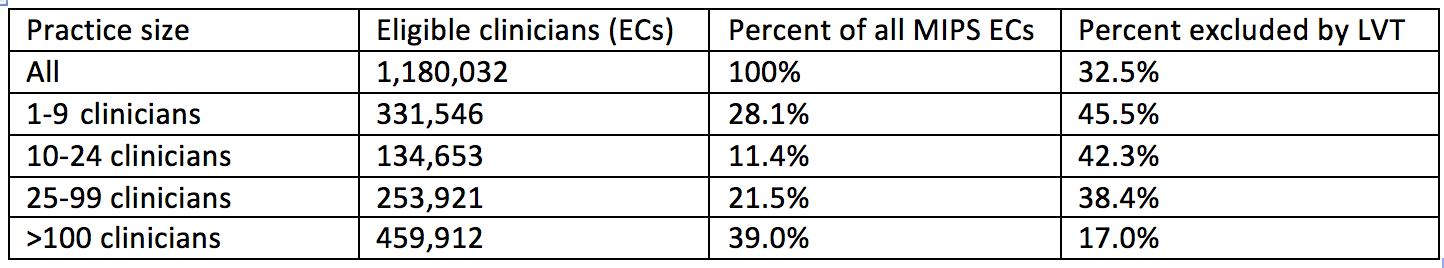

As you may recall, Health and Human Services has the opportunity to exclude eligible clinicians from MIPS based on the volume of services they deliver to Medicare beneficiaries. The original MACRA final rule published last fall set the LVT at either $30,000 of Part B allowable charges OR 100 Medicare beneficiaries. Bill less than $30k or see fewer than 100 Medicare patients during this year and you are excluded from MIPS in 2017. There’s a cool table in that original final rule (Table 58), which estimates the percentage of eligible clinicians the LVT is expected to exempt from MIPS this year. Globally, 32.5% of all eligible clinicians would be excluded in 2017.

The neat thing about this table is it breaks down the exclusions by specialty. There are 40 specialties listed in the table. Not surprisingly, the table suggests that only 15.4% of the nephrologists eligible to participate in MIPS would be excluded due to the existing LVT. Only 6 specialties listed in the table had a lower percentage excluded from MIPS due to LVT. Think about this for a moment. Given the unique relationship ESRD has with Medicare coverage, our specialty receives a disproportionately high share of practice revenue from Medicare when compared with the universe of providers. Raising the LVT as proposed will certainly remove more providers from the MIPS program, but they are unlikely to be nephrologists.

Small practices

Fast forward to the 2018 proposed rule. “We propose several policies for the Quality Payment Program Year 2 to reduce burden. These include raising the low-volume threshold so that fewer clinicians in small practices are required to participate in the MIPS starting with the 2018 performance period.” Read that statement again very carefully. In the eyes of CMS, the driver behind raising the LVT is to exclude small practices from MIPS. Does that make sense to you as a practicing nephrologist? Do you think tripling the Part B allowable threshold or doubling the number of Medicare beneficiaries is going to have a greater impact on small nephrology practices compared with large ones? Where does this kind of logic originate?

Best I can tell it comes from data in Table 59 in the original MACRA rule which I have partially reproduced below for your viewing pleasure.

There are a couple of items of interest here. First, you can make the case that the LVT impacts more providers in practices with less than 10 providers compared to practices with more than 100. And there’s a noticeable trend as you move from small practices to large. But let’s face it, the differences between 1-9 and 10-24 are trivial at best.

Second, notice that 60% of the MIPS eligible clinicians are in practices with more than 25 providers. Difficult to believe that’s the case for nephrology, and yet remember in the eyes of MIPS we are all counted together.There are a couple of items of interest here.

Finally, if your intent is to remove small practices, why not simply remove small practices? Trying to slay this dragon by increasing the LVT has the unintended consequence of removing small primary care practices while leaving small specialty practices to compete with the mega practices that dominate the landscape.

$90,000 or 200 patients

The current LVT was expected to exclude 382,252 eligible clinicians this year. If the proposed change comes to fruition, CMS anticipates the number of eligible clinicians excluded due to LVT will rise to 585,560. In addition, CMS expects the number of eligible clinicians excluded from MIPS because they are QPs in an Advanced APM will double next year, removing another 180,000-245,000 eligible clinicians from MIPS. If this happens, around 70% of the MIPS eligible clinicians will be excluded from the program next year. Happy days for those excluded? Perhaps. But at some point they are destined to come back into the fold, and when they return, they will face competition from some experienced veterans with several years of MIPS experience under their belts.

What about the shrinking minority that remain in the MIPS game? It’s important to remember that MIPS is a budget-neutral program. With the exception of the $500 million earmarked for “exceptional performance,” the winners are paid by the losers in the MIPS arm of the QPP. Such a zero-sum game creates a performance curve of sorts, manifest as the distribution of the nation’s MIPS composite performance scores (CPS). As noted in Mr. Introcaso’s blog post, excluding 2/3 of the potential participants effectively compresses the MIPS CPS distribution curve. One consequence of this compression is there are fewer dollars to distribute to the winners, or in the words of Mr. Introcaso, you “lose by winning.”

Nephrology numbers

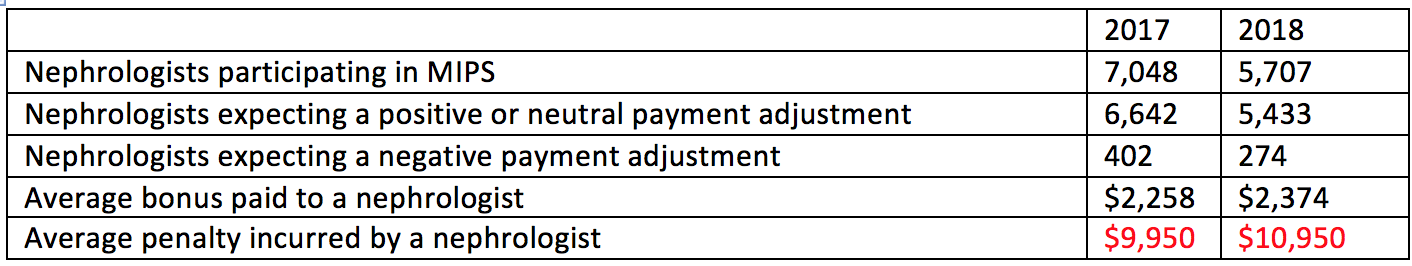

While it’s a bit treacherous to do so, below I have combined the predictions related to nephrologists, harvesting the 2017 data from last year’s MACRA final rule and the 2018 data from the 2018 QPP NPRM.

Notice the number of nephrologists facing MIPS sharply declines in 2018. Although it’s not called out in either document, this is almost certainly due to the rise in participation in the ESCO program and not due to exclusion based on the proposed increase in the low-volume threshold. Also note, that while the number of successful nephrologists is projected to decline, the size of the average bonus changes very little and remains just under 1% of the average nephrologist’s annual Part B allowed charges. What’s remarkable is the lion’s share of this bonus comes from the exceptional performance dollars CMS adds to the program each year, and not from the penalties collected from poor performers within MIPS.

It’s bad news

Given the confluence of factors in the proposed MIPS morass, our specialty will have fewer participants in MIPS in the years ahead, largely due to the rise in popularity of the ESCO program. CMS stated interest in providing relief for small practices is laudable, but raising the low-volume threshold is unlikely to create relief for small nephrology practices, nor for other medical specialties whose case mix relies heavily upon Medicare. In fact, raising the LVT may have the opposite effect because the small nephrology practices will find they are competing against a shrinking field made up of larger and larger general practices.

If there’s a saving grace, it may be the fact that other changes proposed in 2018 are reducing the number of docs who will face a penalty. The percentage of nephrologists expected to see a penalty dropped from 5.7% in 2017 (payment year 2019) to 4.8% in 2018 (payment year 2020). I am a big fan of penalizing fewer docs, but I am intrigued by Mr. Introcaso’s closing remarks. In his eyes, narrowing the field contributes to compressing the MIPS CPS distribution curve. As a nephrologist, how fast are you willing to pedal if the carrot remains so small?

At the end of the day, I firmly believe raising the LVT is bad news for nephrologists. Few additional nephrologists will be excluded from MIPS, and those that remain in the MIPS game will face stiffer competition for a smaller pot of money. Other features in the proposed rule (like setting the CPS threshold score at 15 points) may mitigate the risk for nephrologists in 2018, but that’s almost certainly going to change in the years ahead. What are your thoughts about the proposal to raise the low-volume threshold? Drop us a comment and join the conversation.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Image from www.canstockphoto.com

Leave a Reply