For a number of months, I have been spending a lot of time thinking about value-based healthcare. As mentioned in this blog before, we are in the midst of a substantial transition, one that moves us away from being paid for how much we do, to a system that pays us based on how well we do it. This framework is frequently represented using a simple fraction to describe the “value” within value-based healthcare:

For a number of months, I have been spending a lot of time thinking about value-based healthcare. As mentioned in this blog before, we are in the midst of a substantial transition, one that moves us away from being paid for how much we do, to a system that pays us based on how well we do it. This framework is frequently represented using a simple fraction to describe the “value” within value-based healthcare:

Value = Quality/Cost

Every alternative payment model on the books today, as well as the approaching merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) can be framed at some level with this equation. The denominator—cost—is the easiest part of this fraction to measure. It’s the numerator in the value equation that I’d like to discuss today.

Measuring quality

Much has been written about the measurement of quality, and far be it for me to try to summarize that in a 1,000-word blog post. But I would like to highlight a few things.

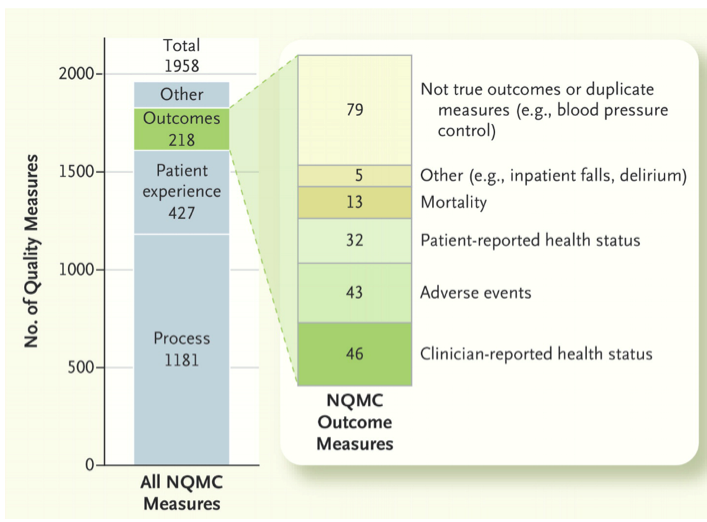

First, the quality programs that are part of the cacophony of alphabet soup, whether ACO, ESCO, BPCI, QIP, MU, PQRS, or the physician VM, are fundamentally in their infancy. The corresponding measures of quality could generously be classified as rudimentary. Out of the gate these programs have latched onto things that are relatively easy to measure. However, you could debate if these early metrics reflect the quality of care delivered or whether our patients consider them important. In last week’s NEJM, Michael Porter and colleagues from Harvard noted that among the 1,958 quality measures listed in the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse, only 136 (7%) were actual outcomes measures and only 32 of those 1,958 were based on patient-reported measures.

Categories of Quality Measures Listed in the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC).1

A bit closer to home, we have the dialysis QIP or 5-Star program, which compels us to measure things like dialysis adequacy and the presence of hypercalcemia. Many nephrologists might argue that adequate dialysis is “table stakes” and others would suggest we are chasing the wrong thing—that instead of Kt/V would should be measuring treatment time and ultrafiltration rates. And while elevated calcium is associated with higher risk of death, this measure finds its way into our pay-for-value program largely because the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) does not have an approved measure for hyperphosphatemia.

The nation’s EHRs

Of course selecting the measures is only half the battle. Capturing the data comes next. Our good friends at the Office of the National Coordinator like to remind us that the vast majority of physicians in this country now use a certified EHR within their office practice. And while it is true the meaningful use program has stimulated EHR adoption, when you look under the covers you may find a few unsettling issues. As ONC ramped up from Stage 1 to Stage 2 and now Stage 3, EHR vendors were forced to meet remarkably tight deadlines in order to make updates available to their physician customer base in time for providers to meet looming MU reporting deadlines. One of the unintended consequences of this time crunch was the ubiquitous appearance of the checkbox.

The checkbox syndrome

I have had the opportunity to see a number of EHRs and I have yet to see one without some form of checkbox. Did you counsel the patient to stop smoking? Check the box. Did you refer the diabetic patient for an eye exam? Check the box. What about reconciling that med list within 30 days of hospital discharge? Yet another checkbox. Don’t get me wrong, the checkbox syndrome is far more appealing than trying to harvest this data from a paper chart. But at the end of the day, is it truly a reflection of the quality we hope to measure?

Extreme examples

Let’s imagine for a moment two different physicians. Doctor A is one of the most accomplished clinicians around and she takes fantastic care of her patients. But she has an obstinate streak about her and either a) does not want to play the checkbox game, or b) spends so much time with her patients that when it comes time to document in her favorite EHR at the end of the day she forgets to check a few boxes. At the other end of the spectrum sits Doctor B, a very savvy young man who knows the rules of this value game. Doctor B checks all of the boxes the night before clinic in order to ease the documentation pain. During the encounter the next day, he unchecks them (when he remembers). Doctor A faces a negative financial impact in spite of being a fabulous clinician, while Doctor B is cleaning up on the financial side of the value equation because he knows how to check a box. While most nephrologists do not live at the extremes, during my travels around the country I have met both of these clinicians and witnessed the unfortunate outcomes.

Clinical guidelines

I’ll leave you with this final point from Porter’s NEJM piece. While unpacking the reasons why we have trouble measuring performance in the quality space, Porter et al note “in health care we’ve allowed ‘quality’ to be defined as compliance with evidence-based practice guidelines rather than as improvement in outcomes.” Many of our checkboxes are chasing practice guidelines, but as noted in the graphic above, the vast majority of these guidelines involve moving the needle on process measures, not true outcomes.

I recently had the pleasure of hearing Dr. Ann O’Hare speak about Geriatric CKD and ESRD. Ann referenced the “tyranny of guidelines” and made the case that the blind pursuit of practice guidelines is problematic. Much has been written about this issue, with perhaps the biggest concern being that the typical practice guideline is written to address the “average” patient and as we all know we rarely encounter the average patient.

What matters?

As value-based healthcare evolves, I think we will find the checkbox syndrome less important. We may discover we are measuring the wrong thing. Next time you are in a dialysis facility, think about whether the patient in front of you cares more about his Kt/V or whether or not the care team treats him with respect. Empathy and hope are difficult to measure, but patient experience of care and patient satisfaction surveys are getting closer to this flame. Hospitals have figured this out. Patients expect the care to be good, but almost as importantly they wonder why someone needs to turn the light on at 4 am to empty the trash can or refill the paper towel container.

The measurement of quality is evolving. The clinical metrics you and I grew up with remain important, but they are increasingly becoming table stakes in the world of value-based healthcare. Patients are more interested in survival, quality of life, and functional status, and those are things that require more than simply checking a box.

Reference

1Porter ME, et al. Standardizing Patient Outcomes Measurement. N Engl J Med 2016;374:504-506.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Leave a Reply