Today’s catchy title may invoke memories of that risqué movie from the 80’s starring a young Tom Cruise famously dancing in his tidy whities. But today’s post is not about that type of risk. Instead we are going to spend some time with a risk adjustment model that’s quietly become an important part of most of the payment programs nephrologists are involved with today. The name of this program is a mouthful: The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hierarchical Condition Category risk adjustment model, thankfully shortened to CMS-HCC risk adjustment.

Today’s catchy title may invoke memories of that risqué movie from the 80’s starring a young Tom Cruise famously dancing in his tidy whities. But today’s post is not about that type of risk. Instead we are going to spend some time with a risk adjustment model that’s quietly become an important part of most of the payment programs nephrologists are involved with today. The name of this program is a mouthful: The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hierarchical Condition Category risk adjustment model, thankfully shortened to CMS-HCC risk adjustment.

Medicare Advantage (MA)

Before we take a dizzying dive into risk adjustment, let’s explore the origins of the HCC framework. The story starts with insurance, specifically Medicare Advantage. Medicare beneficiaries have long had the option of choosing alternatives to standard Medicare. In 1997, this option became known as Medicare + Choice. In 2004, the program underwent another name change and Medicare Advantage as we know it today was born. Today, about 1/3 of all Medicare beneficiaries choose Medicare Advantage over traditional Medicare.

MA plans are typically operated by commercial insurance companies. Medicare pays these plans a sum of money, which the plans then use to pay claims to hospitals, doctors, dialysis organizations, and all the other providers involved in delivering care to Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in the MA plan. One of the fundamental questions, of course, is what’s a fair price to pay for the delivery of that care? How does Medicare determine how big the check should be that they write to pay the MA plan every month? As we will see later, the answer is the HCC risk adjustment model.

Insurance 101

Have you ever heard a doctor say something like “my patients are sicker”? This type of banter occasionally comes up when someone is searching for an explanation for ending up on the wrong side of a quality score. Risk adjustment is an attempt to solve for this, and believe me when I say it’s not perfect. Historically, the HCC model was intended to solve this problem for another reason. Think about insurance for a moment. Each of us (or our employers on our behalf) buy health insurance as a safety net. We are willing to spend a little money up front in order to avoid paying for that rare healthcare disaster that could financially bankrupt the average individual. By design, the vast majority of people in the insurance-risk pool pay a premium that is higher than the health care expenditures they will consume. But each of us is willing to “overpay” as a trade off for the protection against that potential catastrophic risk noted above.

Now think about those MA plans. If Medicare simply said, let’s count up all the money we spent on Medicare patients last year, divide that by the number of patients we insured, and that average dollar figure is the amount we will pay the MA plans, we would quickly have a problem. MA plans would (or perhaps I should say could) modify their benefit designs in such a fashion as to make them less attractive to “sicker” patients (imagine a plan that had a very high co pay to see a specialist…do you think the typical renal patient would join that plan?). Preventing this type of “cherry picking” requires an objective method to identify which patients will consume more medical services and which will consume fewer. Enter the HCC risk model.

HCC

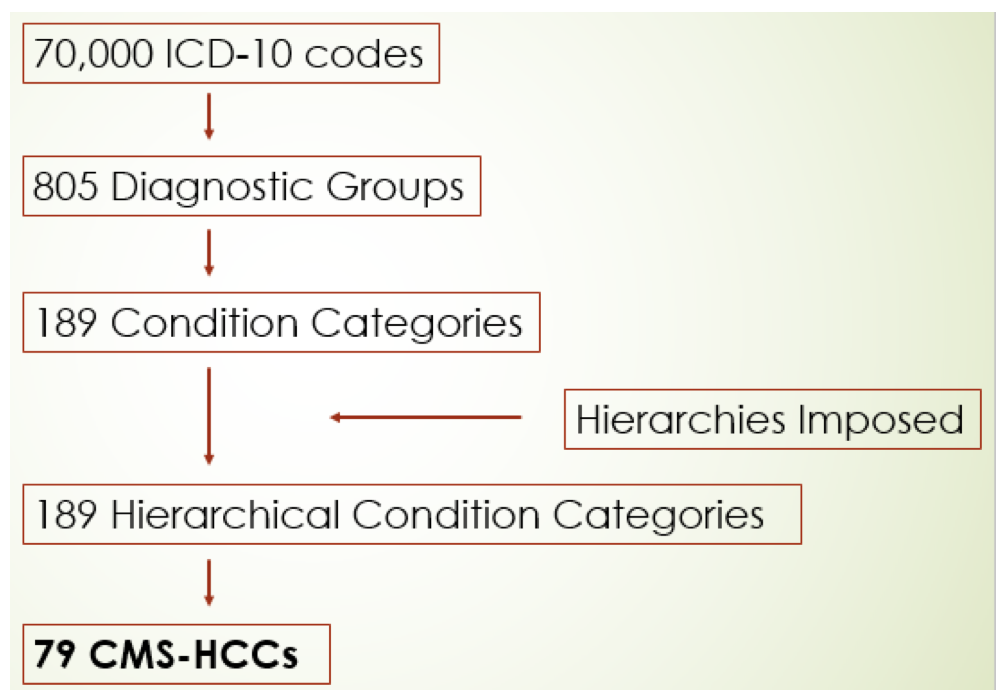

The approach taken by HCC goes something like this: A patient’s risk score is made up of a combination of demographic factors (age, sex, etc.) and the patient’s major medical conditions. Recall there are roughly 70,000 ICD-10 codes. Those codes are assigned to one of the 805 “diagnostic groups.” Each diagnostic group (DXG) represents a well-specified medical condition. The 805 DXGs are rolled up into 189 Condition Categories (CCs). The DXGs within a CC are related both clinically and with respect to costs. Next, the framework invokes Hierarchies. For example, there are 3 diabetes condition categories:

- HCC 17: Diabetes with acute complications

- HCC 18: Diabetes with chronic complications

- HCC 19: Diabetes without complications

If a patient with diabetic neuropathy (HCC 18) develops diabetic ketoacidosis (HCC 17), the Hierarchy selects the “riskier” HCC and the patient receives the HCC 17 risk score instead of the lower HCC 18 risk score.

So, now we have 189 HCCs. A team of smart people (actuaries) then examine data sets consisting of over 1 million Medicare beneficiaries, and using complex logistic regression techniques, they identify the HCCs that best explain the cost of providing care to this patient population. Today’s version of the CMS HCC framework uses 79 of the original 189 HCCs.

The HCC Funnel-adapted from RTI International

Back to MA

The Medicare Advantage program uses HCC in a “prospective” fashion. That is to say, Medicare examines a patient’s claims experience this year in order to predict next year’s costs. Another interesting tidbit you should know about risk scoring is that it is truly an annual process. For example, assume you provide care to Mrs. Smith, a type 2 diabetic with retinopathy and peripheral neuropathy. If during the course of the year, none of the providers caring for Mrs. Smith submit a claim containing a diagnosis for diabetes, in the eyes of the CMS HCC risk adjustment model, Mrs. Smith no longer has diabetes. MA plans spend a lot of time ensuring this does not happen, in large part because they know that as a diabetic with chronic complications, Mrs. Smith is likely to incur greater medical expenditures during the year, than will a patient of similar age who does not have diabetes. If an appropriate diabetic ICD-10 code does not make its way to a claim during the year, the MA plan will not be paid enough to cover Mrs. Smith’s anticipated cost of care.

But wait, there’s more

I highlight the HCC program, not because of MA, but because this risk adjustment model is now part of many of the tentacles we face in MACRA. Anyone in the Acumen blogosphere participating in an ESCO? Risk adjustment, along with trend, are the only two things that impact your local financial baseline. As a provider, you have no impact on trend in the ESCO program, but you certainly influence risk scores because you submit ICD-10 codes on the claims you send to Medicare. How about our new friend the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)? Yes, HCC plays a big role in MIPS as well. Let me share two specific examples.

Recall the new “complex” patient bonus? CMS decided that for at least this year, those participating in MIPS and caring for “sicker” patients should be eligible for up to 5 additional points above and beyond the base MIPS score. Those 5 points come from a combination of the relative percentage of your patients with Medicaid and the risk score your patients receive via HCC. Importantly, patients seen by nephrologists have the highest HCC scores among every other medical specialty.

The second important area within MIPS where the HCC framework is invoked is within the cost category of MIPS. This year, the cost category consists of 2 specific metrics: total per capita costs and Medicare spend per beneficiary, a proxy for hospitalization costs. In each of these, the patient’s HCC score is used to risk adjust the metric.

Risky business

The ultimate goal of risk adjustment is to level the playing field, to recognize that patients with additional disease burden will, on average, incur more costs than will patients with a lower disease burden. Importantly, risk adjustment is not perfect, and at the individual patient level, it’s far from perfect. Within a specific category, the current risk adjustment model explains about 12% of the differences seen in patient expenditures. (This is a population model, not one for use at the individual patient level.) Almost 4 decades ago, the American Academy of Actuaries summed it up like this:

“Determining average experience for a particular class of risk is not the same as predicting the experience for an individual risk in the class. It is both impossible and unnecessary to predict expenditures for individual risks. If the occurrence, timing, and magnitude of an event were known in advance, there would be no economic uncertainty and therefore no reason for insurance.”

As nephrologists, it’s important for us to realize the pervasive nature of the CMS-HCC risk adjustment model. Historically, the billing and coding focus in the transactional fee-for-service environment we’ve all grown up in has been directed at ensuring our documentation supports the CPT code we submit to a payer. Increasingly, it’s the ICD-10 codes on the claim that matter. Gone are the days when simply submitting a single ICD-10 code was sufficient. If you address Mrs. Smith’s diabetes during a visit with her, make sure you document it and add the appropriate ICD-10 code to the claim you submit. If you do not, CMS may think Mrs. Smith no longer has diabetes, and that’s risky business.

What are your thoughts about risk adjustment? Drop us a note and join the conversation.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Image from www.canstockphoto.com

Mahesh Allam MD says

The best summary on HCC & Risk Assessment I have seen.

It’s imperative for physicians to understand these concepts as we are in the best position to diagnose & prioritize.

My only concern is the payments are directed to administration with the crumbs to the providers

Dominique Carpentier MD says

Nice summary. I don’t understand why chronic conditions that can’t resolve have to be captured in office visit notes each year when diabetes with complications can’t resolve. It makes the cynic in me wonder if this is Medicare hoping for some”breakage” (the term used for rebate money that does not get claimed and is kept by the seller. The busy physician fails to capture a diagnosis that calendar year and so loses money that she should rightfully be given.

My other concern is the possible abuse of identifying who are the patients that are expected to cost the system more.

Jody C says

Physicians must continually document and code chronic conditions for quality of care. It shows that they know and understand the patients conditions and are evaluating and treating all conditions thoroughly at least once per calendar year. All conditions must be supported with diagnostics and treatment plans.

It is called a CMS RADV audit. That is how to avoid fraud and abuse.