I recently attended a seminar offered by a local functional medicine doctor. I was intrigued to learn about a practice that operates solely on private pay patients—or what I like to call “boutique medicine.” Her agenda for the evening was supposed to cover alternative, holistic methods to healing the body of common diseases such as high blood pressure, anxiety, diabetes, and obesity.

I recently attended a seminar offered by a local functional medicine doctor. I was intrigued to learn about a practice that operates solely on private pay patients—or what I like to call “boutique medicine.” Her agenda for the evening was supposed to cover alternative, holistic methods to healing the body of common diseases such as high blood pressure, anxiety, diabetes, and obesity.

However, it quickly spun into a night of bash-the-insurance-companies.

Her biggest issue was with payers defining her value based off their perception of quality of care—thus focusing on metrics and hitting numbers that she did not always find relevant.

By the end of the evening I was given a scare-tactic sales pitch that required I either drink the juice (to the tune of $7K for a 6-month care plan) or forever fall victim to the world where doctors are no longer in control of defining what constitutes quality of care.

So why did I tell you this story? Well, everything always relates back to MIPS, of course! Although the whole event was a bit extreme, there were some valid points about how current measures may not be truly meaningful.

Most measures not valid?

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) set a goal that 90% of all Medicare fee-for-service payments will somehow tie to value and quality by the end of 2018. With this aggressive goal, one would hope the definition of “quality” would be well-defined and proven.

A survey conducted in 2016 found that U.S. physician practices collectively spend $15.4 billion each year in order to report quality measures! Whether it be to commercial payers, government agencies, or other independent organizations this breaks down to approximately 785 work hours ($40,000 annually) per physician! In the same survey, 63% of physicians reported that the current measures they are reporting do not capture the quality of care that the physicians provide.

In response to the survey, the Performance Measurement Committee (PMC) of the American College of Physicians (ACP) developed a set of criteria to help test the validity of some high-use measures and published their results last month in the New England Journal of Medicine.

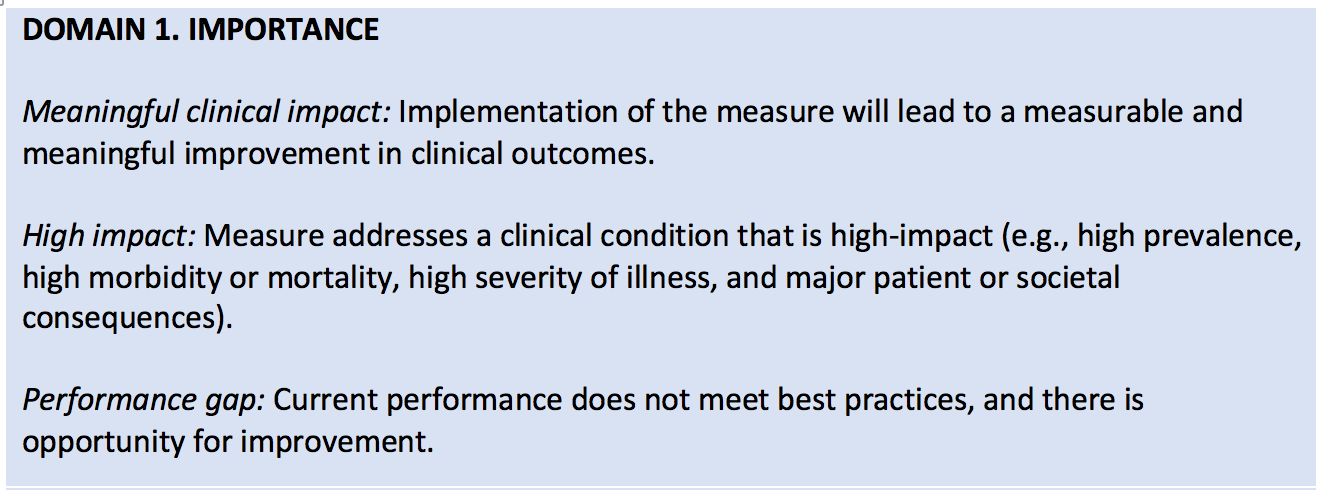

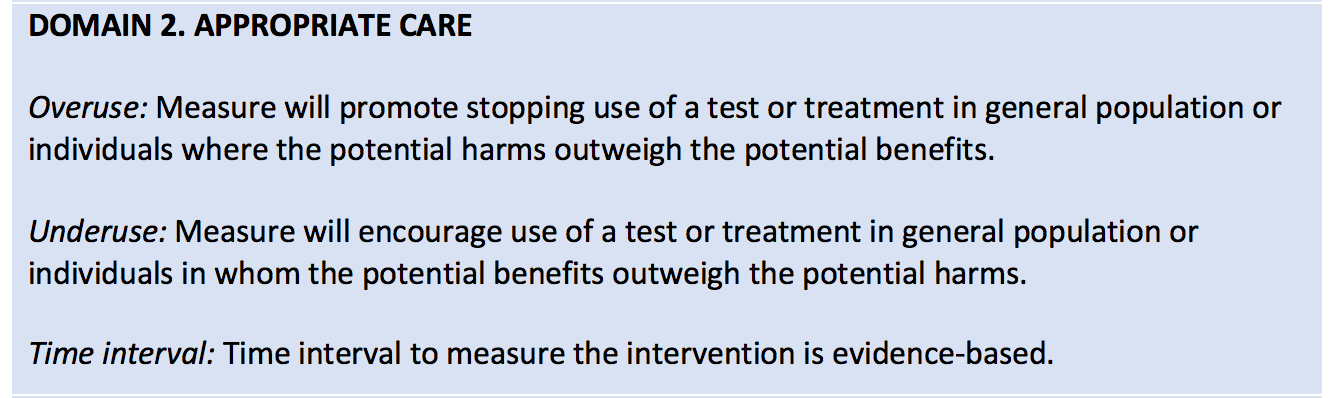

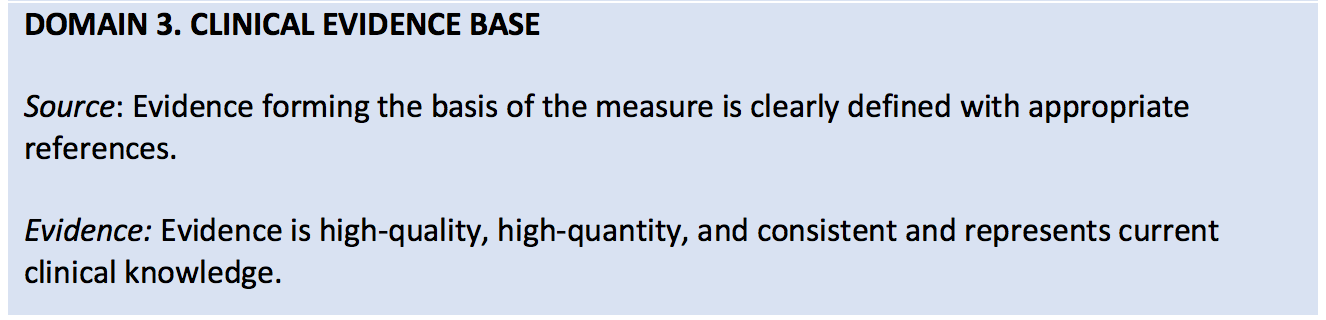

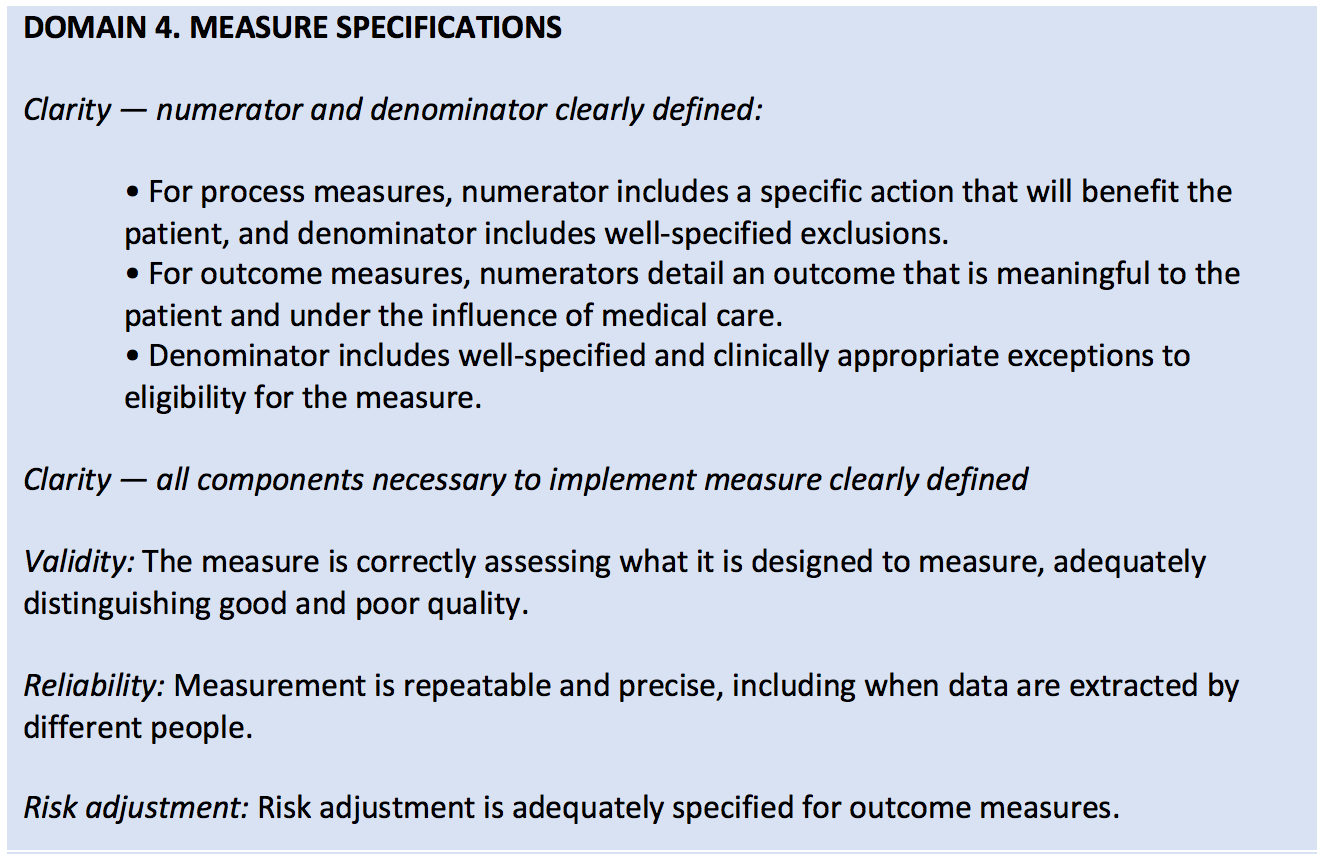

The ACP developed criteria in 5 domains (found in the table below) to assess the validity of performance measures—blending both the clinical relevance of a measure along with the burden and feasibility of data collection.

Of the 271 measures found on the 2017 QPP measures list, the ACP identified and selected 86 measures that it considered relevant to general medicine. Of the 86, the ACP found that only 32 (37%) of these measures were rated as valid! The remainder were marked as not valid (35%) and of uncertain validity (28%).

What were some major findings?

- There was insufficient evidence to support the measure.

- Measures were not endorsed by larger organizations.

- Inadequately specified exclusions resulted in a requirement that a process or outcome occur across broad groups of patients, including patients who might not benefit.

Of the three findings above, I found the last one the most troubling and relevant to the world of nephrology. Let’s take the MIPS measure “Controlling High Blood Pressure” as an example. It requires that a blood pressure of <= 140/90 mm Hg be achieved for hypertensive patients. However, it doesn’t exclude frail, elderly adults or patients with certain complex coexisting conditions where forcing down the blood pressure could do more harm than good.

As you can imagine, there are more stories like the one above for other generic measures that clinicians are using today.

Time out!

After the alarming results of the study, the ACP has called for a time out to assess and revise our approach to physician performance measurement:

“The use of flawed measures is not only frustrating to physicians but also potentially harmful to patients. Moreover, such activities introduce inefficiencies and administrative costs into a health system widely regarded as too expensive.”

Their suggestion is for developers, assessors, and public and private payers to adopt a more rigorous method of assessing measures’ validity that would identify potential problems before the measures are launched. For example, allowing all measures to be tested with a single set of standards and by clinicians who have expertise in clinical medicine and research.

If MIPS measures assessed were deemed valid using this process, clinicians may have more confidence that adherence to the measured practices would result in improved patient outcomes. On the other hand, if some substantial proportion of the measures were deemed not valid, the results would suggest the need to change the process by which MIPS measures are developed and selected.

In addition, the ACP called for more flexibility in future performance measurement systems and advised policymakers to implement standards that aren’t “limited by the use of easy-to-obtain data” and that function “as a stand-alone, retrospective exercise.”

What do you think about changing the process of measure creation? Is there a bigger issue at play? Can we truly improve the quality of care through performance measurement? Or should we all drink the juice?

We would love to hear your thoughts and experiences in the comments!

Diana Strubler, Policy and Standards Senior Manager, joined Acumen in 2010 as an EHR trainer then quickly moved into the role of certification and health IT standards subject matter expert. She has successfully led Acumen through three certifications while also guiding our company and customers through the world of Meaningful Use, ICD-10 and PQRS.

Diana Strubler, Policy and Standards Senior Manager, joined Acumen in 2010 as an EHR trainer then quickly moved into the role of certification and health IT standards subject matter expert. She has successfully led Acumen through three certifications while also guiding our company and customers through the world of Meaningful Use, ICD-10 and PQRS.

Image from www.canstockphoto.com

Leave a Reply