Last Monday I opened up the Renal & Urology News update to find 3 recent articles about health IT (HIT) security. The first article, “Controlling Access to Health Information”, noted that the number one HIT security risk for organizations is having a proper policy in place, but not following the policy in practice. Health and Human Services (HHS) imposes substantial monetary fines on organizations that have an HIT security breach for failing to follow policy. The other articles reported that in recent years misplaced mobile devices have also resulted in millions of dollars in HHS fines, and the Office of Civil Rights often adds an additional Corrective Action Plan (CAP) burden to the HIPAA breach monetary fine. A recent HIT security breach at South Florida Memorial Healthcare Systems involving a former employee who continued to use log-in credentials to access Protected Health Information (PHI) for over a year after employment termination resulted in a $5.5 million fine.

Last Monday I opened up the Renal & Urology News update to find 3 recent articles about health IT (HIT) security. The first article, “Controlling Access to Health Information”, noted that the number one HIT security risk for organizations is having a proper policy in place, but not following the policy in practice. Health and Human Services (HHS) imposes substantial monetary fines on organizations that have an HIT security breach for failing to follow policy. The other articles reported that in recent years misplaced mobile devices have also resulted in millions of dollars in HHS fines, and the Office of Civil Rights often adds an additional Corrective Action Plan (CAP) burden to the HIPAA breach monetary fine. A recent HIT security breach at South Florida Memorial Healthcare Systems involving a former employee who continued to use log-in credentials to access Protected Health Information (PHI) for over a year after employment termination resulted in a $5.5 million fine.

Cybersecurity: Protected information

Health IT security breaches can be costly in many ways, including money, disruption of operations, and impugned reputation with a loss of public trust. As much as we need good hand washing in health care, we also need good “cyber hygiene”. This means that health care organizations should:

- Actively manage IT vulnerability

- Pursue frequent technical testing

- Address IT network weaknesses

- Keep hardware and software up to date

HIT experts suggest that we are likely to see continued malware attacks, so your health IT security should include organizational firewalls, secure webmail and email gateways, and software for virus and malware detection.

HealthIT.gov offers robust online cybersecurity information with the “Top 10 tips for cybersecurity”:

- Establish a secure culture

- The weakest link is the User who lacks awareness about threats and vulnerabilities

- Be vigilant for risks of unauthorized disclosure and alteration or destruction of Protected Health Information (PHI)

- Don’t think “it can’t happen to me”; it can happen to you

- Address these risks with training, policies and procedures, and checklists

- Protect mobile devices

- Mobile health (mHealth) brings opportunity and new security threats

- New mHealth security issues include:

- Device loss or theft

- Data corruption through electromagnetic interference

- Unauthorized viewing when the mobile device is used in a public space

- A requirement for strong authentication and access controls, especially password protection

- The need for encrypted wireless data transmission

- Maintain good computer habits

- Maintain and update software

- Attend to User accounts

- Immediately remove access to data from Users who are no longer part of the organization

- Organize proper disposal of hardware

- Use a firewall

- Prevent Internet threats from entering your secure IT environment

- Install and maintain anti-virus software

- Because it’s difficult to prevent entry of software viruses, routine sweeping and clean-up are required

- Plan for the unexpected

- Natural and man-made disasters happen (i.e., fires, floods, hurricanes, earthquakes)

- Maintain protection from loss with daily backups and data recovery plans

- Control access to PHI

- Have a robust HIT access control system that maintains Users and assigns User rights

- Individual Users need to have “permissions” to see certain files, or role-based access controls should be in place to permit groups of employees file access

- Have a robust HIT access control system that maintains Users and assigns User rights

- Use strong passwords and change them regularly

- This is the first line of defense against unauthorized access to a device and the PHI stored on the device

- Not only is a strong password structure needed, but regular changing of passwords must be required

- Limit network access

- Secure a wireless network and encrypt data transmissions

- Control physical access

- 50% of data loss cases reported to the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) occur secondary to loss of a physical device

- This includes loss of flash drives, laptops, and handheld devices like smartphones and iPads

- Secure physical devices behind locked doors or in areas without unauthorized access as much as possible

- 50% of data loss cases reported to the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) occur secondary to loss of a physical device

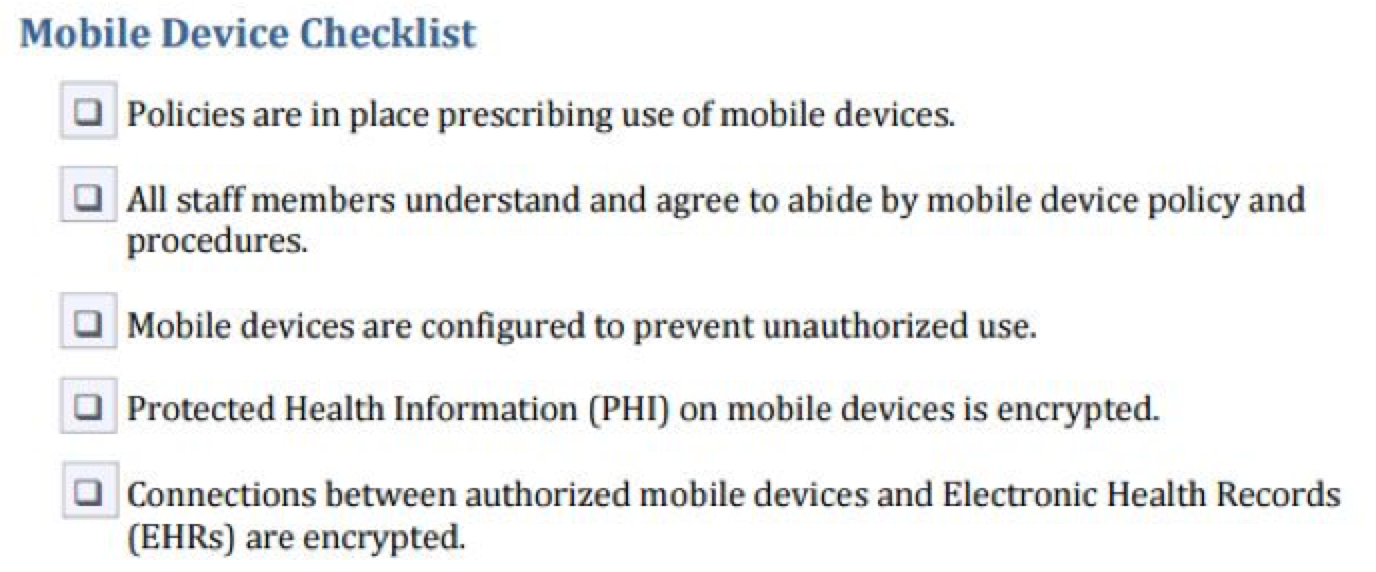

The HealthIT.gov website provides details on all of these tips and offers a link to download and print checklists for each of these cybersecurity activities. As an example, here is the “Mobile device checklist’:

Blockchain: Secure access

On one hand we are working hard to create HIT data security while on the other hand we need access to data to deliver coordinated health care. How can we secure data while expanding access to it?

One solution may be the blockchain. Blockchain emerged in 2009 as the foundation for online trading of bitcoin currency. In basic terms, the blockchain treats every digital transaction as an individual block and the blocks are linked together in a “ledger” which is the chain. The “ledger” has a verification process, meaning that it is maintained automatically without any third party permissions, additions, or verifications. The integrity of the ledger is maintained by a “mining” process that links the blocks in the chain. This includes a complex mathematical puzzle that creates a unique “hash” or letter/number sequence that is developed using the “hash” of the previous block.

Blockchain is a distributed network with a shared “ledger,” securely and immutably capturing digital transactions. Some blockchain features include:

- Connects unrelated or independent parties to a cohesive, shared repository. In the health care context, blockchain would make data shareable among payers, billing departments, patients, and providers

- Provides a permanent transaction record of digital activity

- Acts as a distributed network that can be accessed for secure transactions

- Enables transaction security through cryptography and transaction approvals

- Verifies every transaction through a “mining” process

- Provides real-time data access to every independent entity through the distributed network—as soon as a new block is added it is visible to all those with access to the blockchain

- Allows all types of data to be added to the blockchain, including data from personal devices like wearable sensors

Recently a lot has been written about the use of blockchain technology to meet HIT security needs while also supporting interoperability or data-sharing requirements for improved health care delivery.

In a recent Harvard Business Review article, Dr. John Halamka, geekdoctor blogger and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center CIO, wrote:

“The rationale for considering a blockchain in electronic health care records is twofold. First, it avoids adding another organization between the patient and the records. It is not a new clearing house or “safe deposit box” for data. The blockchain implies a decentralized control mechanism in which all have an interest, but no one exclusively owns it. This is an architectural change that generalizes past medical records. Second, it adds due consideration to a time-stamped, programmable ledger. That opens the door for intelligent control of record access without having to create custom functionality for each EHR vendor. The ledger also inherently includes an audit trail.”

HIT security is the responsibility of every health care organization today. Make sure you complete your security risk analysis. Have good policies in place to provide role- or individual-based access to PHI in your organization. Make sure members of your organization are following your policies. Use good cyber-hygiene and stay informed about new technologies like blockchain that may make tight data security and data sharing more compatible.

If you have cybersecurity stories or tips to share with other nephrologists, please leave a comment. We’d appreciate hearing from you!

Dugan Maddux, MD, FACP, is the Vice President for CKD Initiatives for FMC-NA. Before her foray into the business side of medicine, Dr. Maddux spent 18 years practicing nephrology in Danville, Virginia. During this time, she and her husband, Dr. Frank Maddux, developed a nephrology-focused Electronic Health Record. She and Frank also developed Voice Expeditions, which features the Nephrology Oral History project, a collection of interviews of the early dialysis pioneers.

Dugan Maddux, MD, FACP, is the Vice President for CKD Initiatives for FMC-NA. Before her foray into the business side of medicine, Dr. Maddux spent 18 years practicing nephrology in Danville, Virginia. During this time, she and her husband, Dr. Frank Maddux, developed a nephrology-focused Electronic Health Record. She and Frank also developed Voice Expeditions, which features the Nephrology Oral History project, a collection of interviews of the early dialysis pioneers.

Image from www.canstockphoto.com

Leave a Reply