“That will be 148 dollars and 52 cents.” Thus began my odyssey into the world of pharmacy benefit managers, while standing at the counter of the local branch of a national pharmacy chain last weekend.

“That will be 148 dollars and 52 cents.” Thus began my odyssey into the world of pharmacy benefit managers, while standing at the counter of the local branch of a national pharmacy chain last weekend.

It’s been a very light week at the intersection of nephrology and health IT. So today, loyal blog readers, allow me to entertain you with a personal story.

Without exposing too much PHI, yours truly is a reasonably fit, middle-aged male (OK, perhaps I am taking liberties with the middle-aged description) who has been fortunate enough to not require chronic mediations to date. Last weekend I developed a minor acute illness that required medical attention. I live in a small town, and as a physician, I have a bit of an unfair advantage when it comes to navigating the morass of urgent visits with health care providers. After a very satisfactory encounter, a diagnosis was rendered, and a script made its way electronically to the aforementioned nationally recognized pharmacy. Confident that my employer’s health plan had me covered, imagine my surprise when the script for 30 tablets of a generic medicine first discovered by the ancient Greeks was going to cost me around $5 a pill!

Part of my day job allows me to rub shoulders with some very bright minds, and in my moment of disbelief, a couple of neurons fired, and I asked Jeff (in a small town we know the pharmacists by their first name), how much is the brand name med? Back to the computer he went and the answer? Fifteen bucks for those 30 pills. To Jeff’s credit, the local pharmacy was not trying to pull the wool over my eyes. The rules require them to hard code their computer system to pick the generic unless the prescriber specifically orders the brand, because most of the time, that’s the less expensive alternative.

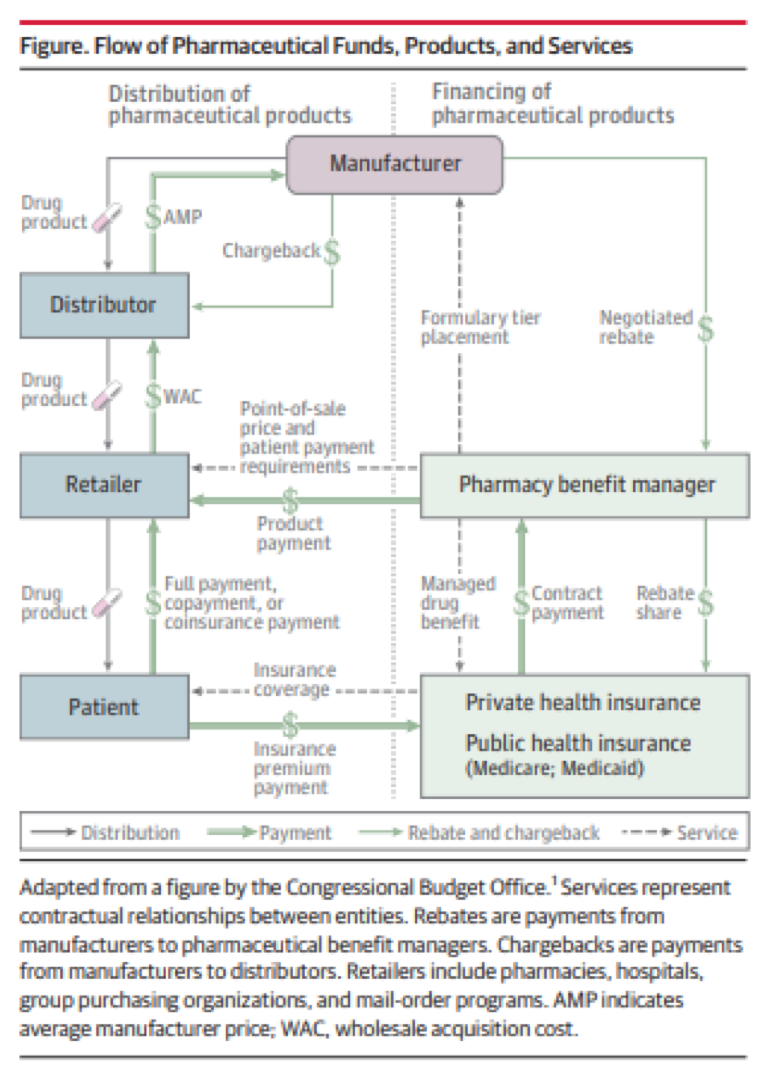

Think about this for a minute. My out of pocket for the generic was $5 a pill, while the brand was 50 cents a pill. How is this possible, you ask? Well, as they say, it’s complicated. Our journey to unpack this story starts with a complex figure published in JAMA last year by Dr. Kevin Schulman, one of my former teachers in B school. This 2-pager is an interesting read, and one I highly recommend if you have an interest in such things. It also begins to shed some light on the out-of-pocket dilemma I faced last weekend.

As astutely pointed out by Kevin and his colleagues, “The flow of pharmaceutical products from manufacturers to distributors to retailers to patients evolved separately from the financing mechanisms for the same products.” Talk about setting the stage. Remember that old saying “follow the money”? That’s actually quite difficult to do in the figure above because rebates and chargebacks in this “value chain” are private transactions, the design and magnitude of which remain opaque to you and me.

Pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs)

PBMs are powerful intermediaries that sit between patients, health plans, and pharmaceutical manufacturers. They play a prominent role in the figure above. I suspect, but of course have no proof, that the odd circumstance I encountered last weekend has a lot to do with rebate arrangements between the drug manufacturer, the PBM, and my health plan. The out-of-pocket expense I faced was designed to drive me toward the brand-name drug. That only happens if the folks making the rules stand to gain financially when I pick brand over generic.

Don’t get me wrong, PBMs play a key role in ensuring we have access to the medications we need and that we can get them in a timely fashion. PBMs have also been in the news a lot of late. Cigna recently announced it was purchasing the large PBM ExpressScripts, and CVS, which owns the large PBM Caremark, recently announced its intent to acquire health insurer Aetna. Perhaps coincidentally, Kevin and his colleagues authored another PBM related viewpoint in JAMA, published within days of my encounter with the world of pharmacy benefit managers. This one is worth the couple of minutes it will take you to read. One fun fact from Kevin’s latest piece; PBMs generate a lot of revenue, in some instances they generate more revenue than the pharmaceutical companies most of us are familiar with.

The FDA

Let me conclude by saying PBMs are not necessarily the sole cause of my anguish last weekend. Part of the blame lies at the feet of the FDA. The saga related to the medication in question also involves an unintended consequence, which followed a move made by the FDA when it introduced the Unapproved Drug Initiative. You see, the med prescribed for my ailment (and used successfully for centuries) had never before been tested in a rigorous fashion. Following the introduction of the unapproved drug initiative, all prior generics for this medication ceased to exist, and in their place emerged a single-sourced brand product. Oh, and the price? It went up about 2,000%.

The future?

Drug prices are receiving quite a bit of public scrutiny these days. Mergers and acquisitions in this space are creating a lot of speculation regarding what may come next. My crystal ball is rather cloudy in this arena, but it’s probably not a huge leap of faith to believe we could see significant changes in this morass in the years ahead. As Kevin notes in his latest piece, the migration toward value-based care may foster some of this change. In the meantime, the next time the price for your generic med seems a bit high, ask them what they charge for the brand name…you may be glad you did.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Image from www.canstockphoto.com

Leave a Reply