A few weeks ago we started a discussion about the Physician VBP. This week I’ll be taking a deeper dive into this relatively new CMS incentive program. I’d like to apologize at the outset for the length of this post, as it is easily the longest in my four-year blogging experience.

A few weeks ago we started a discussion about the Physician VBP. This week I’ll be taking a deeper dive into this relatively new CMS incentive program. I’d like to apologize at the outset for the length of this post, as it is easily the longest in my four-year blogging experience.

As you may recall, 2014 is the performance period for the 2016 VBP for physicians practicing in a group with 10 or more providers. Although the VBP is only applied to the physician’s payments under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS), your practice’s size is determined by counting any and all of the following folks who bill Medicare using your practice’s Tax ID number:

- Physicians: Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Osteopathy, Doctor of Podiatric Medicine, Doctor of Optometry, Doctor of Dental Surgery, Doctor of Dental Medicine, Doctor of Chiropractic

- Practioners: Physician Assistant, Nurse Practitioner, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist, Certified Nurse Midwife, Clinical Social Worker, Clinical Psychologist, Registered Dietician, Nutrition Professional, Audiologists

- Therapists: Physical Therapist, Occupational Therapist, Qualified Speech-Language Therapist

These 20 provider types will be familiar to regular readers of this blog as they are the same 20 Medicare providers who are eligible to participate in the CMS PQRS program. If your practice includes 10 or more of these folks, you are in the middle of the performance year for the 2016 VBP. If you have fewer than 10 providers in your practice, you will join the fun next year as all physicians are in the game for the 2017 VBP.

What’s the bottom line?

Before we peel back the layers, let’s take a look at the big picture with this tidbit I found in a very nice summary published by the American Osteopathic Association. Late last year, CMS went through a dry run of sorts. They shared cost and quality performance data with almost 4,000 large practices (25 or more providers), based on data collected in 2012. The results:

- 80.7% of these practices landed in the average quality and average cost tiers we discussed last time, so their VBP modifier would have been 0.0% (no penalty, no bonus)

- Almost 11% of the practices would have faced a penalty

- Around 8% would have received a positive bump

Granted these were large practices, but the downside risk in the near term appears low. Couple that with the fact that if you are in a practice with between 10 and 99 providers, and you participate in PQRS this year, there is no downside risk from the VBP in 2016.

Patient Attribution

How are patients attributed to your practice for the purposes of the VBP? Not willing to recreate the wheel, CMS is using the same attribution method they have employed with the Medicare Shared Savings Program to assign a beneficiary to an ACO. This is basically a process that assigns beneficiaries to a group based on who delivered the plurality of primary care services to the beneficiary. Primary care services in this case are defined by CPT codes (99201-99215, 99304-99350) and the welcome to Medicare and annual wellness G-codes (G0402 and G0438, G0439). The American College of Physicians has provided a nice summary of this process.

Quality-Tiering Scoring Methodology

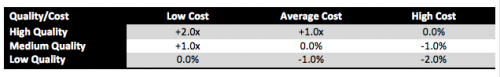

Recall from our previous post, during the performance year CMS is evaluating value by establishing cost and quality composite indices for your practice based on the care the Medicare beneficiaries attributed to your practice during the performance year. Your practice’s cost composite index will be compared with the national mean. If you are within one standard deviation of the mean, you will be classified as “average cost”; otherwise your practice is either high cost or low cost. In a similar fashion, your practice’s quality composite index will be compared with the national mean and your practice will land in one of three quality buckets (low, average or high). The intersection of your practice’s cost and quality indices determine what modifier will be applied to the Medicare PFS for every physician in your practice during the payment year. That assessment in 2014 will be applied in 2016 according to the matrix below:

As noted above, in 2016 only practices with 100 or more providers will face the penalty phase of the program. The maximum penalty those groups could face is a 2.0% reduction in their 2016 Medicare Part B allowable. The “bonus” component of this program is determined as a multiple of “x”. Recall this is a budget neutral program. Bonuses are paid to practices delivering high value using funds collected from practices that deliver low value. CMS will aggregate the funds harvested from those delivering low value, and use that figure in conjunction with the number of physicians in the three buckets due a positive incentive to determine “x”.

Cost

For those of you still reading, let’s take a closer look at the two composite indices, starting with the easier of the two—cost. Costs in this program include Part A and Part B expenses. Drug costs (Part D) are mysteriously absent from these calculations. For the 2016 VBP, your practice’s cost index is composed of three financial measures derived from the Medicare Part A & B costs incurred during 2014 by the beneficiaries attributed to your practice. Those three measures are:

- Total per capita costs,

- A roll up of per capita costs for beneficiaries with four chronic illnesses (COPD, CAD, Heart Failure and Diabetes), and

- A Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary (MSPB) measure. MSPB (like we need another medical acronym) is a metric that basically captures all of the Part A & B costs incurred by a beneficiary during a time period that begins three days prior to a hospital admission and ends 30 days post discharge. The practice which provides the plurality of Part B services during the admission will be the lucky recipient of the MSPB for that admission.

Recognizing we all practice in different parts of the country where expenses are different, and all of us are certain our patients are “sicker” than those cared for by the average provider, the VBP makes an effort to account for both geographic cost differences as well as cost differences attributable to patient risk. They use an accepted Medicare payment standardization methodology to strip out the geographic variations, and they risk adjust the cost index by utilizing the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) model. The HCC model has been in use and refined over the past several years, most notably as part of the Medicare Advantage program.

Quality

Your practice’s quality index will represent a composite of a number of quality-related measures. The component that is best understood is the one related to PQRS. Your practice’s PQRS experience will be evaluated from the perspective of the six National Quality Strategy (NQS) domains. Each NQS domain will receive equal weight as CMS aggregates your practice’s performance scores across the reported PQRS measures in 2014. In addition to PQRS performance, CMS will use claims for care delivered to beneficiaries attributed to your practice and with those claims they will automatically calculate your performance on three hospitalization-related metrics:

- A composite of acute prevention quality indicators (bacterial pneumonia, UTI and dehydration-related hospitalizations),

- A composite of chronic prevention quality indicators (hospitalizations for diabetes complications, COPD and CHF), and

- An all-cause, 30-day readmission measure.

Summary

So where does this leave us? I don’t know about you, but my head is spinning as I reread this post. This is easily one of the most complex CMS programs I have reviewed, and I have reviewed many of them. Several people have weighed in on what seems to be a rush to implement this program when compared with the related hospital VBP program. I think that view was best expressed this past December in the NEJM. Given the complexity, I think it will be difficult for a practice to proactively impact the VBP. My takeaways for practices are these:

- Participate in PQRS this year. Participation in PQRS has been meager to date, but participation will now be required to not only avoid the PQRS penalty, but also to avoid the VBP penalty. What’s more, these penalties are additive. In other words, non-participation in 2014 will result in a 4.0% haircut with respect to your Medicare Part B book of business. Avoiding both penalties today only requires making the effort (participation). Successful reporting of PQRS measures is not required.

- Performance counts. Pay attention to the performance rates for your individual PQRS measures. PQRS began as a pay-for-reporting program in which performance rates were inconsequential. The VBP changes this dramatically as PQRS performance rates are of paramount importance to the VBP program.

- Your practice may not be affected. The vast majority of practices (over 80%) were not impacted in the “dry run” as their calculated VBP was 0.0%. It remains to be seen where this will land when smaller practices are included, but at least out of the gate the impact appears low. In spite of this, please remember if you do not participate in PQRS, you will get hit with the VBP penalty.

- Small provider groups get a break. Groups with 10–99 providers will not have to worry about the 2016 penalty component of the VBP. (You only have upside or no impact in 2016.) At the risk of sounding like a broken record, this assumes you participate in the 2014 PQRS program.

- A few participation exclusions exist. Those of you actively participating in one of the Medicare Shared Savings ACOs, a Pioneer ACO, or the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative can ignore the VBP for now as you are excluded from the 2015 and 2016 VBP program.

- Check your mail. Later this summer CMS will reportedly provide every physician with a Quality and Resource Use Report (QRUR) based on your 2013 data. The QRUR will contain performance on the quality and cost measures described above. Think of this report as your dry run. If you do not review it personally, make sure someone in your practice does.

One final important takeaway here is recognition that CMS is committed to pursuing value. As I mentioned last time, the classic fee-for-service model most of us grew up on is not riding off into the sunset just yet. However, it is clear CMS and other payers are moving away from a transactional-based model that rewards quantity to a value-based model that rewards the efficient delivery of quality. Let’s hope the transition is a smooth one.

Leave a Reply