Have you ever come across the following technique that attorneys sometimes employ when litigating a case? The prosecuting attorney makes an outrageous statement or accusation for all in the courtroom to hear. The defense quickly objects. The judge agrees with the defense and turns to the jury and advises them to ignore what the prosecution said…like it never happened, and it will not influence the jury’s judgement. If you watch closely, you might see the hint of a smile emerge on the prosecutor’s face. Mission accomplished.

Have you ever come across the following technique that attorneys sometimes employ when litigating a case? The prosecuting attorney makes an outrageous statement or accusation for all in the courtroom to hear. The defense quickly objects. The judge agrees with the defense and turns to the jury and advises them to ignore what the prosecution said…like it never happened, and it will not influence the jury’s judgement. If you watch closely, you might see the hint of a smile emerge on the prosecutor’s face. Mission accomplished.

I was reminded of this underhanded technique while reading a recent “perspective” in The New England Journal of Medicine entitled “Dialysis-Facility Joint-Venture Ownership—Hidden Conflicts of Interest.” The authors are from the University of Pennsylvania, a reputable academic institution. Now I know that most Acumen blog readers have their own experience with academic institutions. Heck, most of us were trained at such institutions. We often look to these bright individuals to expand our knowledge through research and teaching. Unfortunately, on occasion they author a piece that’s filled with so many inaccuracies, and poorly disguised false accusations, that one feels compelled to object.

Accusations in perspective

The written perspective is filled with damning statements like “even legally compliant joint ventures…” It seems the authors are implying that most joint ventures aren’t legally compliant. They also suggest “nephrologists might ‘cherry pick’ healthier patients for their own facilities and steer sicker patients away.”

Everyone has a right to their opinion in this country, but when you print something in an Internationally leading medical journal, you should probably get your facts straight first. Near the end of this one-sided perspective is this quote: “Which physicians or physician groups are financial partners in any of the 37 operating ESCOs [End Stage Renal Disease Seamless Care Organizations] is not publicly available information.” Statements like this highlight the isolation that has occurred for these authors within the cocoon of academic medicine. After about 30 seconds and a simple Google search, I came across the public website for the Philadelphia/Camden ESCO. Not only are the docs clearly listed on this website, but the joint ventures are as well. Oh, and the first ESCO participant listed? The University of Pennsylvania Health System. This particular institution itself is an ESCO participant. Do you think the authors know this? Ethical dilemmas in their own backyard? Say it isn’t so!

The authors suggest joint ventures between nephrologists and dialysis organizations create financial incentives that could lead to poor care. So, I thought to myself, could they remotely be right? After all, they are smart people who in the past have figured out things like how electrolytes move across toad bladder membranes (one of my favorite nephrology board questions). In my day job, I am intimately involved in the Fresenius Medical Care ESCO operation. Collectively the 24 ESCOs we participate in account for almost 80% of the Medicare beneficiaries aligned with an ESCO, so according to the authors, I must be one of the most unethical guys on the planet.

ESCO total quality scores

Within our ESCO experience, there are nephrology practices that are substantial investors in the dialysis clinics in the ESCO, and there are ESCOs in which the nephrologists have elected not to be joint venture partners. Does the presence or absence of a joint venture clinic make a difference? Is physician ownership creating the harm the authors’ innuendo suggests? How might we measure that? One objective way to do so would be to divide ESCOs into two groups, one that includes joint venture clinics, and one that does not. (Note one of the states where we operate makes it impossible to be a joint venture partner in a dialysis clinic. In full transparency, in this exercise I have excluded those two ESCOs as the docs in those markets could not hold an equity stake in a dialysis clinic even if they wanted to.)

Each ESCO is compelled to report an ESCO total quality score (TQS) to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services each year. Is the TQS lower in ESCOs with joint venture clinics? Among the 22 ESCOs in this analysis, 15 include at least one clinic that’s a joint venture, and seven have no joint venture clinics within the ESCO. Unfortunately, without the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s (CMMI) approval, I cannot share the actual data with you publicly. I will tell you this—the average TQS in our ESCO programs in 2017 was higher in the 15 markets where joint venture clinics are present (about 4% higher on average).

I will be the first to admit that I am not a statistician, but if the joint venture clinics are creating harm, I certainly do not see it. Let’s take this one step further. Suppose we consider these 22 ESCOs and compare the ESCO TQS with the actual percentage of clinics in each ESCO that has a joint venture relationship with an ESCO nephrologist. What you cannot see until I have CMMI’s blessing to share is a scatter plot that compares ESCO TQS on one axis with the percentage of joint venture clinics in that ESCO on the other axis. Of interest, among the 15 markets with joint venture clinics, there are markets where all of the clinics are joint ventures, and there are markets where a tiny minority of clinics in the ESCO are joint ventures. Bottom line, there is no correlation between joint venture penetration and TQS. In fact, when you look at the two markets with the highest TQS in this analysis, one market had no joint venture clinics, and in the other, every clinic was a joint venture. I don’t know about you, but I am having a very hard time finding evidence in our data that the authors’ concerns are real.

Vascular access centers

Speaking of physician ownership, let’s not leave the vascular access center stone unturned. We not only track the ESCO TQS in our programs, but we publish a transparency report that stack ranks all 24 markets based on how well they perform across a variety of quality metrics. One measure of performance in the transparency report is the ESCO’s 90-day catheter rate. In 2017, two of our ESCOs consistently had 90-day catheter rates south of 5%. The very best was frequently less than 3%. The authors probably do not want to hear this, but guess what? Not only are those two ESCOs full of joint venture clinics, but the access centers in those two markets are owned by the docs. Those unethical souls have better catheter rates than the rest of the country…they must be doing it for the money, right?

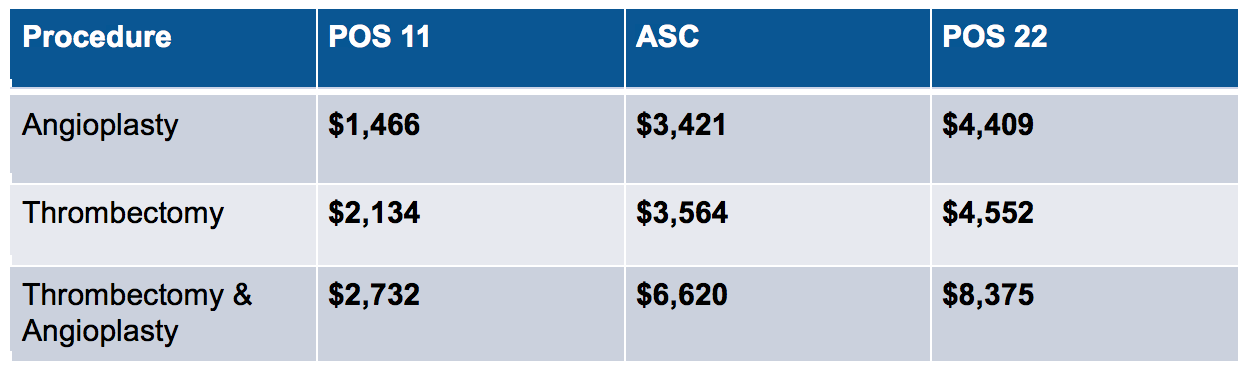

While I am on the access center soap box, feast your eyes on the table below. It includes the price Medicare paid last year for certain vascular access procedures based on where that procedure was performed.

As most of you know, POS 11 is the physician’s office, and yes, just about every POS 11 access center is owned, in part or in total, by a nephrologist. POS 22, on the other hand, is the outpatient department at the hospital, where an academic institution lives. Those two access centers I mentioned above? Both are POS 11. Given the exceptional quality they delivered, if you were a payer, where would you want that work done? With CMS’ slash to reimbursement at POS 11 last year, these centers are under financial pressure. In fact, one POS 11 center within one of our ESCOs closed last month. Guess what that means? All of the access work in that market will now move to the hospital. It will now be substantially more expensive, and much more inconvenient for our patients, to receive access care in that market. Of course, that probably makes the authors of The New England Journal of Medicine perspective happy; the cost of care will go up and patient satisfaction will go down, but at least there’s one less ethical dilemma to worry about.

Adding insult to injury

The authors are no strangers to stooping to the disreputable tactics employed by our fictitious prosecuting attorney. They also wrote a paper earlier this year using the same ill-informed bias to suggest ESCO participants were encouraging high-cost end-stage renal disease patients to stop dialysis, all motivated by profit. The Acumen blog sat on its hands following that one (there were so many errors in their understanding of how the ESCO actually works, we could not have possibly addressed all of them in a single blog post). But one of my colleagues participating in one of our ESCOs was so angry that these authors would question his ethics, that he drafted a response to their article. My colleague is a very bright, hard-working nephrologist who takes care of patients for a living, day in and day out. Guess what happened when he reached out to that journal’s editorial body? They were not interested in counterpoints to the published article. Think about that for a moment. A medical journal, which basically serves as the communications vector for academia, declined to offer balanced editorial practices. I would hate to think medical journals are as interested in controlling the message as they are in advancing the science.

Every physician knows we face ethical dilemmas in our lives. Frankly, in a fee-for-service environment, I am better off financially when I admit a dialysis patient to the hospital, then when I appropriately manage their acute condition as an outpatient, where I am paid less to do so. Does that mean we should accuse nephrologists of indiscriminately admitting end-stage renal disease patients? After all, as noted by the authors, the admit rate and length of stay for this population are both high; perhaps it’s due to the fact that, as a nephrologist, I make more money when someone is in the hospital? This is obviously a ridiculous line of thinking, and it is every bit as absurd as the blatant accusations recently made by The New England Journal of Medicine perspective.

Living in the dark ages

On a final note, consider this. The Stark law was enacted in 1989. As the authors note, dialysis facilities, along with many others, are excluded from Stark. A number of folks at the Department of Health and Human Services are reexamining Stark because they know those rules get in the way of progress. Secretary Azar and team are doubling down on value-based care. They recognize that when the goal is better quality and lower costs, handcuffing providers with a law that was enacted almost three decades ago is not in our patients’ best interests. In contrast, the authors are living in the dark ages, hanging on to vestiges of a transactional fee-for-service framework, and penning perspectives that might have been relevant when I was a teenager.

I suspect it’s easy to sit in the confines of this particular institution and cast stones at ethical, hardworking nephrologists who care for some of the sickest patients on the planet. But I’d encourage these folks to occasionally spend some time on the ground in the real world with docs who deliver care every day. Who knows, that might generate an accurate perspective worth reading.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, practiced nephrology for 15 years before spending the past seven years at Acumen focused on the Health IT needs of nephrologists. He currently holds the position of Chief Medical Officer for the Integrated Care Group at Fresenius Medical Care North America where he leverages his passion for Health IT to problem solve the coordination of care for the complex patient population served by the enterprise.

Image from www.canstockphoto.com

R. Provenzano, MD says

Thank You Terry! I too am fatigued by the assumption that physicians are always up to something sinister and then be asked to prove a negative!

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, Chief Medical Officer - Integrated Care Group says

Thanks Bob, I could not agree more!

Michael Roppolo says

Thanks Terry. I hope this rebuttal is widely distributed. We really need a voice against this type of blatant ignorance.

Brian Michel says

The working assumption that physicians and, for that matter, all professionals in positions of relative power, are motivated only by self interest is one of the top reasons why the country is so divided at present. Accusations are made and the accused are faced with proving the negative which rarely can be absolute. This is just another example but responding in this manner is important and necessary.

Brent Shealy, MD says

Thank you from a private practice group that has JV clinics and was an original ESCO member who works hard every day to provide quality care to the most complex patient group in medicine.

Istvan Bognar says

Right on Brent. We work hard to keep up with the quality care you guys practice down the road. I was sad to see the decay of journalism extend to the NEJM. It is really no place for uninformed op ed pieces.

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA, Chief Medical Officer - Integrated Care Group says

Brent/Michael, thanks for your comments.The response from folks like you who are doing the right thing everyday has been overwhelming. It’s a privilege to write something that resonates with people who provide great care day in and day out.

Mark D. Purcell, DO says

Terry, thank you. I was absolutely disgusted by the publication in the NEJM. In a time where job satisfaction is alarmingly low and nephrologists rank last in terms of whether we would select the same subspecialty again; egregious and inaccurate articles such as Jeffrey Berns have no place. Nor do they help our cause in trying to fill empty nephrology fellowships.

Lisa Maier says

Bravo, Dr. K. Shame on NEJM for stooping to such lows as to publish a poorly researched article that casts aspersions without allowing for rebuttals. In the era of “fake news” one would hope that a reputable, scientific journal would seek to remain above such nonsense.

RG says

Let the record show that the lead author has some public data on the “open payments” website. For example, in 2014 the lead author received 49 payments totaling $4040. The maker of aranesp paid the lead author lots of money. It sounds as though the lead author will need to read the book “Influence” by Dr. Cialdini. If one believes in the evidence, he is the one who is suffering from conflicts. Why is the physician accepting money from a drug company and writing about ethical dilemmas? I think the lead author will need to return his 49 payments of $4040 if he wants to write about conflicts of interest. Why is the “conflict free” physician receiving money from Bayer as well? The “ethical” doctors needs to look in the mirror before he shaves.

RG says

It seems to me the University of Pennsylvania should place on the disclosure statement that they are a participant in an ESCO. Here is his disclosure statement that does not contain this information:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/suppl/10.1056/NEJMp1805097/suppl_file/nejmp1805097_disclosures.pdf

RG says

I don’t the think NEJM disclosure statement was filled out honestly and transparently by Dr. Berns. He is writing an article about conflicts of interest. It is relevant that he has a conflict of interest in his self dealings and needs to disclose that in a transparent manner on the NEJM disclosure form. Is Dr. Berns willing to revise his disclosure form about receiving money from companies? Is there a way to inform the NEJM that the disclosure form has not been filled out accurately? He received 16 payments from companies in the 36 months prior to publication, and this needs to be accurately disclosed on his NEJM disclosure form, not hidden. Here is the link about the 16 payments Dr. Berns has received:

https://projects.propublica.org/docdollars/doctors/pid/107681

Peter Fumo,MD says

The comment at the end:”We make no allegations regarding quality of care or illegal or unethical practices by nephrologists or dialysis companies as a result of joint-venture partnerships” really floored me. They just spent the whole editorial implying as much

Doc O says

The public data goes back to 2013, and the total that Dr. Berns has received is $6,521.29 in payments from private companies. Does Dr. Berns care to share what he received prior to 2013? The problem with the Ivory Tower is that they do not take a multidisciplinary approach to academics. Dr. Berns needs to study the work of Dr. Dan Ariely. The worst kind of conflict a physician, such as Dr. Berns, can suffer from is the one when he does not even know he is being influenced. That is what the cognitive psychology literature demonstrates which Dr. Berns has clearly not read. We know that Dr. Berns is not aware of his conflict because he did not even think to disclose it. I challenge Dr. Berns to write a check back to the companies he received this money from so that he can avoid this conflict that he is not even aware he has.

Physician Tim says

I would ask if Dr. Berns if he has ever attended an ESCO conference call at the University of Pennsylvania? Has he ever spoken with an ESCO coordinator and watched her in action? A professor at such a prestigious university should have the understanding that an educated person should retract a factually inaccurate portrayal of what an ESCO is. I think Dr. Berns needs to spend some more time in the field. He may have a different opinion if he participates in the ESCO that his own University is participating in. The information is so incorrect that additional action is required. Is it possible to take legal action to correct the facts in the article? Is there a way to report the authors to their University board for publishing incorrect information and failing to make proper disclosures?

Dr. Brown says

The author needs to be educated about what it means to be a participant in an ESCO. The author’s medical group can get money from the ESCO (that he is participating in) for a favorable result. Additionally, the author has no down side risk. If the author believes what he is saying, then he is the one with a conflict in his own ESCO. His conflict is even more intense because he can get money from the ESCO and not lose any money. I suggest the author read his participation contract in the ESCO that his renal division is participating in. Common sense says he would do that before he wrote an article like this. The author needs to disclose that the ESCO he participates in earned 12 million dollars in shared savings, and that his employer is eligible to receive a performance bonus as a participant in this ESCO. Unfortunately, the author needs to take note that the physician survey score is below average in the ESCO that his employer participates in. Dr. Berns might focus on physician satisfaction by the patients in his ESCO rather than writing half truths and innuendo that is truly inane. Interestingly, these facts are obtained despite the “hidden” conflict that the author claims to exist. One could argue that the authors are showing their stupidity. This is like renting a car and then writing a paper on what a terrible rental car this is—-yet drive the car every day and have a favorable result with the car (12 million in shared savings). The authors should be ashamed of their lack of knowledge and poorly written piece.

Terry Ketchersid says

I want to thank all of those who have sent us comments, and thank the countless number of people who have responded privately. As one of my colleagues noted this evening, the author continues to publish articles suggesting nephrologists are making unethical choices motivated by financial incentives.

https://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/early/2018/10/10/ASN.2018040438

In the Acumen blog’s 8 year history, there has not been a more robust response to a single post, highlighting the importance of this topic. Thanks again for your continued support of the blog.