While I was away last week a colleague forwarded an article that addresses an issue receiving increasing attention. As the CMS meaningful use program gains traction and a larger number of providers implement and adopt electronic health records, some are asking if the use of template-driven EHRs is leading to a shift in provider coding patterns.

As most of you are aware, the OIG has been very interested in “cloned notes.” You know the ones I am talking about; you sometimes see them in the hospital or from referring physicians. Cloned notes tend to pull forward a tremendous amount of detail from the previous patient encounter; detail some would argue is not pertinent to the current patient encounter. Related to cloned notes is this issue of upcoding. Under scrutiny is the following question: Does template-driven documentation lead to the capture of excessive detail, which results in billing for a higher level of service?

In the article cited above, Jonathan Blum, Deputy Administrator and Director for CMS, states there is no evidence to date to support a correlation between EHRs and upcoding, but, “We have begun efforts to study whether there are differences in coding patterns for those who have adopted EHRs versus those who have not.”

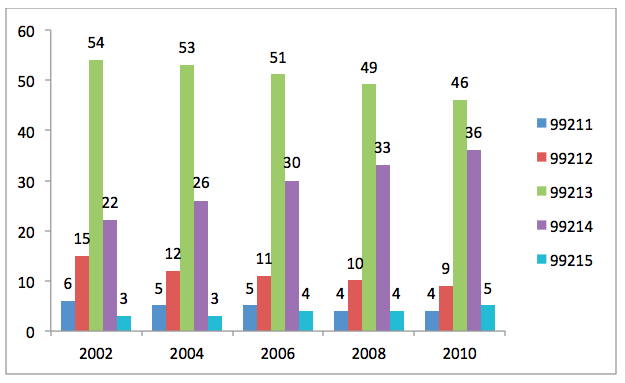

Could this be a classic case of “which came first, the chicken or the egg?” EHR adoption rates are clearly on the rise, but the shift in coding patterns appears to have predated the widespread adoption of CEHRT. According to the ONC, EHR adoption rates among office-based providers was 17% in 2008, increasing to 25% at the end of 2010. In May of 2012, the OIG released a report entitled, “Coding Trends of Medicare Evaluation and Management Services.” Below I have put their numbers for office-based follow-up encounters into a bar graph. The graph displays the distribution by percentage among the five levels of service available for office-based follow-up care among Medicare Part B beneficiaries. Note the decline in 99213 and the rise in 99214 over the date span in this graph. To my untrained eye the shift towards higher codes started long before EHR adoption rates began to climb. By the way, the graph looks the same for new patient encounters, subsequent inpatient hospital care, ER visits, and a host of other code groups.

Medicare Part B beneficiaries: Office-based follow-up encounters by service type from 2002-2010

Part of the challenge is deciphering the less-than clear set of guidelines we are compelled to use when determining the level of service. Approaching 30 years of age, the 1995 and 1997 AMA coding guidelines, while written in black and white, occasional appear as multiple shades of grey, particularly under the scrutiny of a coding audit. Although I have made a habit of attending a nephrology-specific coding class every year, when the topic of E & M coding comes up, my eyes glaze over and my head begins to spin.

As Dr. Steven Stack, chair of the AMA Board of Trustees points out in the article referenced above, medical records were once designed to capture the provider’s findings and decision-making process. A patient’s record served as a point of reference for the provider and as a communication tool when collaborating with others involved in the patient’s care. Over time the medical record has morphed into a document that serves several other masters, including billing, coding, compliance and litigation.

Has EHR adoption been accompanied by a shift to the right in coding patterns? I suspect the answer is yes. Of course, historically physicians have been more likely to under-code and one could argue this trend represents a long overdue correction. However, if there is a message in this added scrutiny, I think it pertains to the cloned note. The copy and paste or auto-populate features available in almost every EHR on the market are popular time savers, but we need to be judicious in their use.

Leave a Reply