Readers of this blog are no doubt familiar with the complexities of providing medical care to patients with End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD). This patient population suffers with significant comorbidity and requires substantial medical attention. Within this context, these vulnerable patients consume a relatively large proportion of health care dollars on a per capita basis. Not surprisingly, the provision of care to this population is among the most scrutinized in the U.S. health care system.

Dialysis providers had an early seat at the CMS value-based purchasing table as the ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP) was deployed several years ago. Unlike the physician value-based payment modifier, the QIP only offers downside risk: do well and keep your Medicare payment, do poorly and receive a reduced payment. Dialysis providers have also had early exposure to CMS’s drive towards transparency. Dialysis Facility Compare, which predated Physician Compare by several years, is readily available in the public domain. Further, CMS compels every dialysis facility to post its QIP results so patients may see how the facility performed against CMS’s standards for good quality care.

A spirit of cooperation

The renal community, including patients, nephrologists, and dialysis providers, has a history of working closely with CMS. Recent examples include broad input with respect to the establishment of the QIP and the ongoing development of its quality measures, and the construction of the payment bundle itself. But on July 10, this cooperation took a hit when CMS unilaterally announced a new dialysis 5-Star rating system. On a conference call unveiling the program, CMS staff appeared to shroud themselves in the cloak of cooperation by inviting patients, physicians, and providers alike to submit comments on the new program. But this invitation was severely compromised by the admission later in the call that CMS would not use any of the community’s comments to make changes to the program when it goes live in October. Not exactly the transparent spirit of cooperation we have been led to believe underscores the ESRD program.

On the surface, the dialysis 5-Star rating system sounds like a fabulous idea. Leveraging a symbolism utilized in everything from automobile safety to hotel and restaurant rating schemes, using one star to represent poor quality and five stars for outstanding quality is simple and easy to understand. The fundamental error CMS made, however, involves the curse of the bell curve.

Origins of the bell curve

The tale of the curse began in the 19th century when the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss codified a remarkably useful tool. Referred to by a number of names through the ages, a Gaussian or normal distribution is a statistical concept that allows one to sample a population and make a reasonable estimate regarding where one might land. Graphically the distribution looks like a bell, which provides the springboard to our common reference of the “bell curve.” One critical assumption inherent in this tool is that the variable you are attempting to estimate is “normally” distributed. Notice two important features here: first, this tool got its start because it filled a need to determine probability in the face of uncertainty, and second, it only works if the variable under study has a normal distribution.

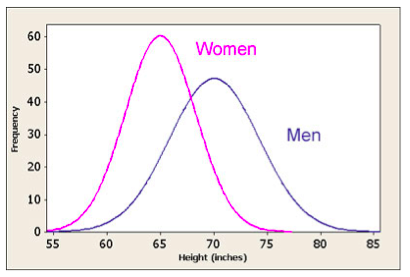

The world is full of examples where this model works reasonably well. One example is the height of men in the U.S. The average height of an adult male in this country is 70 inches (5’ 10”). I am 73 inches tall (6’ 1”). The fact that height follows a normal distribution means I can comfortably assume there are just as many folks in this country that are my height as there are men who stand 67 inches tall (5’ 7”). Further, the normal distribution tells me there are far fewer adult men who have reached my neighbor’s stature (79 inches or 6’ 7”), but there is a decent chance there are as few men who stand 61 inches tall (5’ 1”). If I am in the business of selling men’s clothing, knowing that men’s height fits a bell curve provides me with valuable insight.

The curse

There are also a multitude of examples where the bell curve fails miserably. In the financial space assumptions based on a normal distribution have brought about catastrophic consequences, even for people one might assume should know better, including Nobel Prize winners Myron Scholes and Robert Merton. Organizations also sometimes use a bell curve to determine merit increases. The flawed assumption here is that the organization hires to the bell curve, only expect 5% of its employees to be top notch, and expects another 5% to be so bad they will be sent packing. The sad truth is, in many companies, there are far more people in the top performer group than the bell curve permits rewarding.

Some of us also painfully remember when obstinate college professors insisted on using a bell curve to establish grades. For example, suppose everyone in the class scored above 85 on a test. Even though the scores indicate all of the test-takers are at a B level or above, invoking the bell curve requires some to fail. If CMS were grading that test, 10% would fail and another 20% would receive a D.

The Bell and 5 Stars

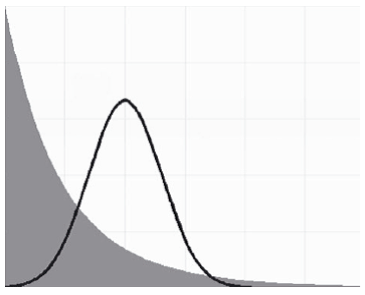

Screwing this up in college or when preparing to pass out merit raises is one thing, invoking the curse in health care scares the daylights out of me. With the soon-to-be-released dialysis 5-Star rating system, CMS is cramming a distribution that looks something like the grey section of the graph below into the bell curve.

The Bell Curve and a Pareto Distribution

Imagine you are a 55-year-old diabetic dialysis patient with an above-the-knee amputation. Your dialysis facility is doing a great job. You like the staff, and although you don’t understand the QIP, you take comfort in the knowledge that your facility, your second family, did great on CMS’s quality measures and did not face a QIP penalty. Out of the blue, and without explanation that you can understand, your facility receives two out of five stars. How does that make you feel? As your nephrologist, I could explain the flawed math behind the stars until the cows come home, but will you sleep better at night?

The really sad thing about the 5-Star program is that it’s actually much worse. The inappropriate application of a normal distribution to variability we know is not normally distributed is compounded by the incorporation of ratios in the calculation. I’d have to take my shoes off to clearly illuminate the problem here – and it’s clear the statisticians at CMS left their shoes on for this one – but the ratios like standardized mortality and standardized hospitalization each come with a confidence interval. Think of the Gallup poll for a moment: “In a recent Gallup survey, 65% of voters would repeal the Affordable Care Act.” The fine print always defines the confidence interval (plus or minus 3% with 95% confidence). Bottom line, there is uncertainty buried in those ratios. Force them into a normal distribution and the curse intensifies.

Lifting the curse

This nightmare could have a happy ending. Although it does not appear likely, CMS could lift the curse at the 11th hour. Perhaps we will all wake up in a cold sweat and discover it was only a bad dream. If the curse is not lifted, however, history is very likely to repeat itself as what is a well-intentioned, but poorly reasoned idea will almost certainly create unintended consequences. Nassim Taleb, successful investor and the author of The Black Swan, is well acquainted with the curse of the bell curve. Quoting from Dr. Taleb’s best seller, “When you develop your opinions on the basis of weak evidence, you will have difficulty interpreting subsequent information that contradicts these opinions, even if this new information is obviously more accurate.”

The question is, Is CMS listening?

Leave a Reply